The University Receives Us

Dortmund, May 17, 2018

Our event in Dortmund, Germany was at the University of Dortmund International Begegnugszentrum. We’d been referred to Dr. Walter Gruenzweig, Professor of American Literature and Culture, by our friend and American editor Liz Rosner.

First Rudi’s impressions

Professor Walter Gruenzweig introducing Rudi and Julie

When I was in high school, I had a barely passing grade in English. Now, here many years later, find myself introduced as a co-author of a book, as part of the American Studies Lecture Series, by a professor to students, as many as 170, some sitting on the floor because there were no more chairs. It was an odd feeling. One could speculate that the old teachers I had, who survived in their teaching positions after the Nazi empire collapsed, were unable to teach or were unable to inspire because in retrospect one could say the potential was there in me.

Rudi and his former student

Some student even had to sit on the floor

A former student of mine—from when I returned to Germany in 1972-73 to teach in my old high school—was at the event. He was sitting in the first row. He approached us afterwards and told Julie that being my student was one of his best experiences in school. Ironically, I was his English teacher.

A compelling story

Before the event started, Julia Sattler, a colleague of Professor Gruenzweig, told us a compelling story about her family. She’s probably in her thirties now. She said that all during her childhood, she believed her grandparents were in the resistance. When she was 20 years old, she learned that it wasn’t true. They were members of the Nazi party, although not influential in any way. She described herself as being very angry. She was particularly outraged at the thought that they had done nothing to fight back or speak out against the Nazis.

Research on Rudi’s father

This a side note to the actual presentation: for years on and off we’ve been doing Google searches and other kinds of research on Rudi’s father. One perplexing question we always had was what his Nazi Party rank of Hauptbannfuehrer really was. When I was a reporter, I encountered a fellow at the Hoover Institution who was a German military expert. Rudi and I made a special trip to Stanford to talk to him but we came up with no answers.

Signing books and chatting. The students all wanted the American version of the book

We thought of this in Dortmund when Professor Gruenzweig told Rudi his father was easily searchable on the Internet and gave him two examples: one was a certificate attesting to a student’s proficiency in Latin written on the letterhead of the Adolf Hitler Schule in Sonthofen and signed by Rudi’s father, the Director. It was being offered for sale on eBay for 130 Euros.

The other item of interest was a chart the professor had listing ranks in the Nazi party and their equivalents in US military terms. Hauptbannfuehrer was a major general. Dr. Gruenzweig wondered how he had achieved such a high rank in his thirties.

Fact and fiction

And finally and very respectfully, Dr. Gruenzweig pointed out two errors of fact in our fictional description of Gerhard. In our book, as Gerhard is fleeing Germany, he hitchhikes to Prague and makes his way to the train station. He doesn’t speak Czech and he tries to blend in without being discovered. The professor said Prague in those years was an international city and many languages were spoken. Another scene has Gerhard in a pub in Austria where he overhears a group of students making derogatory statements about the Nazis. Gerhard is draw to them. Dr. Gruenzweig said that even before Germany invaded Austria, things were very repressive and students would not be making inflammatory comments in public places.

It’s another reason why it’s a good thing our book is fiction, although certainly it would have been better to have gotten those details right. Next time.

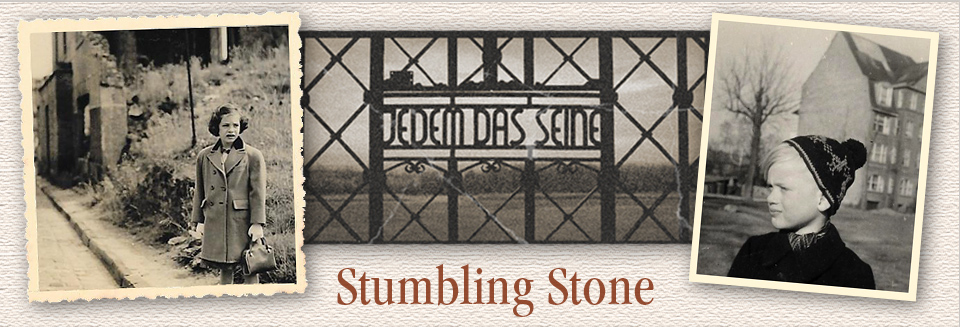

Julie Freestone and Rudi Raab are taking a three-day break from their book tour with Der Stolperstein to visit family in Dusseldorf.