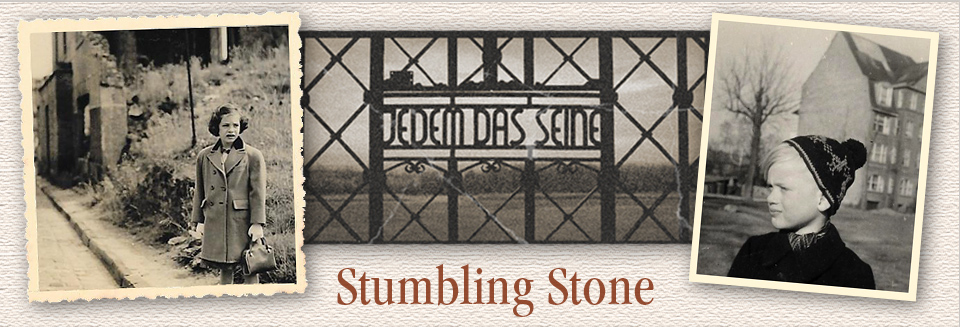

A Catholic School Leads the Way

Stop Three: Speyer, Germany

Auditorium at Edith Stein Gymnasium in Speyer

They were lined up on the stairs and along the windows in the auditorium, more than a dozen teenage girls, whispering to each other and looking at us — leaning over a table and signing and selling books on the stage.

It was a surprising end to a presentation we did at Edith Stein Gymnasium (high school) in Speyer, Germany. When Rudi said at the end of our hour-long presentation and question-and -answer session that we had books to sell, no one moved. I figured Rudi had been right in encouraging me to take very few books into the school. After all, they were teenagers who, if they read at all, probably used electronic devices. But then, suddenly, there was a near-stampede. I didn’t have to say “I told you so,” because Rudi had to sprint back to the car for the rest of the books we had with us.

When we had driven up to the school that morning, a little in advance of our start, we knew nothing about it. When we googled it, we discovered it was a Catholic school. We had gotten the invitation in a very convoluted way and only learned afterwards that Karin Togler, who had suggested we speak there, was a graduate.

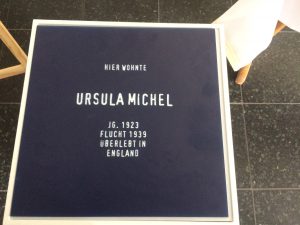

Students are raising money for a Stolperstein for Ursula, who survived the Holocaust

When the principal Andreas Kotulla and Annette Meuser, a teacher there, took us on a brief tour, we understood why the students – 190 of them – responded with such heartfelt comments about what they thought of our reading.

First, the school is named after Edith Stein, who was born into an Orthodox Jewish family, became a women’s rights activist and a nun and was murdered in Auschwitz. Besides that, the school is part of the Speyer Stolperstein Coalition, a group of organizations working to install stumbling stones in the city. The school is raising funds for theirs to commemorate Ursula Michel, a local Jewish girl who fled on the Kinderstransport and was saved. As students filed out of the auditorium after we read, volunteers were soliciting contributions. The Gymnasium also has a display in the school lobby about Jewish history in the area. One particularly moving element was the replica of a suitcase on the table with a book – Packed and Ready to Go.

Poignant display at Edith stein Gymnasium

Although the students listened in total silence and with rapt attention as we told our story and read from the book, no one said anything at first when we asked if there were any questions. Then, one brave girl asked what our parents thought of our romance. That triggered a series of thoughtful comments and questions.

One especially interesting one was whether Rudi had suffered from having a Nazi father. He said no. I used the opportunity to talk about our friend and colleague Elizabeth Rosner’s book Survivor Café. We explained the concept of inter-generational trauma that might be felt by even the great-grandchildren of Holocaust survivors and others who suffer from violence.

I wish I’d put on my reporter hat and asked those teenage girls what it was about our story that resonated with them. I was too busy signing books and making change.

Julie Freestone and Rudi Raab are touring Germany with their novel Der Stolperstein, translated from the American version Stumbling Stone. The book is a literary memorial to Rudi’s Uncle Gerhard Raab, who was murdered by the Gestapo.