Searching for Answers: Where is It? Chapter I

By Julie Freestone and Rudi Raab

For the next two days, the blog will make a detour from observations about the reality of shelter-in-place to a little jog into semi-fiction. For years, when we went on vacation, we would sometimes come home and indulge ourselves in writing a grade D novel most of which we never finished. One memorable one was “Lost in the Lava Tube”, inspired by a trip to Crater Lake.

Nothing to do with CoVid yet

Lost in the Lava Tube was inspired by a vacation to Crater Lake

After we took the boat ride on the lake and made the short climb up the hill, a crazy idea for a fiction account began to crystallize in our banter: What if during the boat ride, the lake began to churn and landslides crashed down the crater walls into the lake? You would immediately think “large earthquake”. And what if the lake level began to subside? Where would all the water go? Perhaps the large earthquake is a huge collapse of the magma chamber which erased the volcano and created the lake originally. And perhaps a huge lava tube which had been plugged for untold thousands of years opens up. The lake drains through the tube into Klamath Lake.

The boat (which we had just been on) finally gets sucked into the miles long dark tube and somewhere runs aground. All passengers are now “Lost in the Lava Tube”. And then you have the bimbo in high heels (it’s a Grade D novel, folks) slowing every attempt to escape. This would be a movie, maybe playing on a Central Valley TV station at 3 a.m. between used car commercials.

We actually wrote about eight chapters and we actually had an independent movie producer interested in selling it until he realized how god awful it was. (He taught us the term “fem jep” – female in Jeopardy – which he thought he could pitch it as)

Not our first rodeo

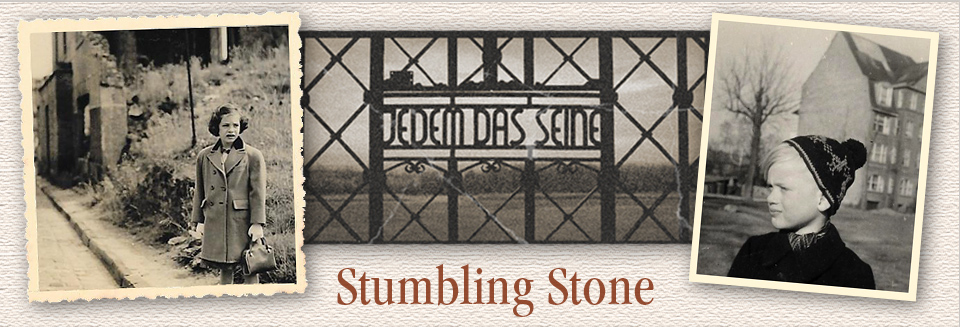

We spent three weeks once at our cabin writing a torrid romance about two cops in a rural area. Our novel Stumbling Stone probably originated in part from one of these frivolous writing exercises and then the book evolved into something more serious. Even though it’s a novel, we say it’s about 90% based on true information. And Lost in the Lava Tube has some geological integrity.

Today we’re going to take you with us on one of our fiction efforts born during this shelter-in-place. You decide how much of it could be true.

Chapter One

It began innocently, accidently, maybe mindlessly. Two retirees having their evening cocktails, watching the news. Turning off the sound when ads came on, making dinner in between. They didn’t even, at the beginning, comment on the piece about a new disease in China. Who cared? They weren’t going there and there were always new diseases.

It began innocently, accidently, maybe mindlessly. Two retirees having their evening cocktails, watching the news. Turning off the sound when ads came on, making dinner in between. They didn’t even, at the beginning, comment on the piece about a new disease in China. Who cared? They weren’t going there and there were always new diseases.

Neither of them was sure when they began listening more carefully. It might have been when Wolfgang saw the shots of heavily armed soldiers in China. He was a retired cop. Those kinds of images usually caught his eye. It might have been when Susan noticed that all the newscasts were leading with this story. She had been a news reporter before becoming the communications officer at a local health department. She made a sport of trying to predict what would be the lead story each night. It might have been when the cases of the new disease——now called CoVid 19—began appearing and sky rocking in Italy and then in New York City and a local county. And it certainly was when the World Health Organization declared that the outbreak was a pandemic. Susan had begun calling it that a week before.

It was a Thursday night about 5:15 when Wolfgang yelled to Susan, who was in kitchen, “Come quick. Look at this.”

The TV reporter, an old friend of theirs, was standing outside a local hospital, explaining that there had been a dramatic increase of local cases and that health workers and other front line staff were complaining about the lack of protective gear for them and the shortage of ventilators for patients.

Wolfgang and Susan looked at each other. How was that possible?

He was the first to speak. Lately he had been expressing concerns about memory loss. Was it natural for someone in his mid-seventies to forget things or was it the start of dementia?

“Where is the Strategic National Stockpile,” he said. “Isn’t that what it was called? That project I worked on?”

After retiring as a street cop in a local city, Wolfgang had been hired briefly by Susan’s health department to write a federally required plan. It described in great detail how the county would request, pick up, store and disperse the very equipment the news said wasn’t available.

“Yes,” she said tersely. “I worked on it too. Remember the drill we did? With the local police department to test your plan. Where is that stuff?”

In the next few days, while it became obvious that no one seemed to remember or know about the SNS, Wolfgang dug up his approved plan and Susan began contacting reporters to alert them to the SNS. No one seemed much interested. There was too much happening—more deaths each day, outbreaks where there had been no cases, wild promises from the White House, grim press conferences by governors, announcements of ever-more restrictive policies.

Confined to their house, Susan and Wolfgang grew more distraught each day. Doctors working without masks, patients struggling to breathe.

“We have to find the SNS. Let’s just assume that someone at the state level, or the county level or somewhere knows about this and has requested the shipment. There must be a reason they are keeping it a secret,” Wolfgang said. “Let’s go find it.”

Susan laughed but she knew he wasn’t kidding. He liked high risk situations and she remembered he’d once been involved in an exercise to test the security of a Coast Guard station. Wolfgang had scoped the area a day before and found a very high fence which went into the water and a large gate. He got himself a tide chart at a bait shop and found the time of very low tide.

The next day, with the help of two busloads of Coast Guard recruits from Modesto who were dressed like “60s radicals”, he organized a loud demonstration at the locked gate. A few pallets were stacked up and a little fire was lit. The alarmed Coasties brought in a fire engine. While everyone watched the firefighters, Wolfgang and three students went slowly to the waterline (it was now low tide) and walked past the fence. They were inside the perimeter and had “won the war”. It was fun and exciting. She figured he was itching to do something like that again.

“Before we get involved in this, why don’t I contact Lee and see what she knows?” Lee Strong had been the health official who hired Wolfgang to write the SNS plan. She was a family friend and she had been hired by the federal government a few years before. They weren’t really sure what her job was now. They stayed in touch; sometimes she spent holidays with them. Lee answered the email quickly but was surprisingly unforthcoming when Susan asked, “Do you remember the SNS? Where is it?”

“Of course I remember the SNS. Things are crazy here. You can’t believe some of the BS that’s going on.” That was the end of Lee’s email.

“That’s not an answer,” said Wolfgang. He looked at Susan. “This could be the story of your career.” He smiled. They had been together for three decades. He knew which buttons to push.

“I’m retired,” she said unconvincingly. “I have no career.”

Wolfgang pulled out the DVD containing the plan. “Let me show you where I think the stockpile for our county should be. We can start there. We don’t have to do anything yet. We can just take our daily walk, but make it be around the perimeter of where it should be stored. See if anything unusual is happening there. I’ll give up if we don’t see anything.”

Next: Chapter Two: Reconnaissance

Rudi Raab and Julie Freestone published their novel Stumbling Stone in 2015. They wrote Homecoming, an unpublished romance about two cops in rural Northern California.