The Jews are Gone but the Synagogue is There

Stop Six: Altenkunstadt, May 6, 2018

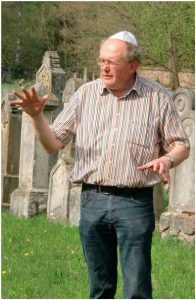

Josef Motschmann lived in Altenkunstadt, a small German village of 3,000, all his life. As a boy born in 1952, his parents told him they had once had Jews as neighbors. He noticed that no one talked about those times. So he set out with a tape recorder and began interviewing Altenkunstadt’s residents about the war years.

Josef Motschmann

Few people wanted to talk to him, but some did. He asked specifically about what happened on November 9, 1938, referred to for many years as Kristallnacht and now called by some the November Pogrom. Some residents he talked with told him about how Altenkunstadt synagogue was destroyed. They even told him the names of the perpetrators.

Rebuilding the synagogue

Josef, who died last year, went to Israel with a youth group. A teacher, he then set out on a mission to restore something of the local Jewish community. He created a grassroots coalition to raise money and eventually succeeded in collecting $2 million. On the site of the burned-out building, the group rebuilt the old synagogue, where we did our book event.

Twenty-five years ago, the building was dedicated. “The Jews were gone but the synagogue is here,” said Josef’s wife Fritzi Fischer

Friedrich Edelmann, Rebecca Rust, Fritzi Fischer and Inge Goebel at the Altenkunstadt Synagogue

The dedication ceremony in 1993 drew Jews who had been driven from the community but survived the Nazi concentration camps. They came from as far away as Israel. Relatives of victims who were murdered also came. And workers from the government office that collected drivers’ licenses from Jews in 1938 also came. In a drawer in their offices, they had found the revoked licenses. They gave them to a nearby high school, which assigns students to research the lives of those long-forgotten Jews and create a public exhibit.

You have to talk about it

Inge Goebel, a retired teacher who has volunteered for a number of years at the synagogue and its museum, said “People here lived with the Jews, they knew what happened, they didn’t want to talk about it, but you have to talk about it.” Among the many compelling items in the museum are hidden papers with Jewish prayers and other writing that were found in the beams of the homes of the Jews who were deported.

Snippets of papers found in the beams of former Jewish homes

A final word about Josef Motschmann. He was a Catholic theologian with a passion for history. Each year on the anniversary of the date the Jews of Altenkunstadt were rounded up and deported, he organized a march, from the spot where they were made to congregate, to the train station. He insisted on reading the names of each Jewish resident. He took care of the Jewish cemetery in Altenkunstadt. When Altenkunstadt celebrated its 1200th anniversary, he was asked to write a history of the Jewish community. He said he would do it only if he could name names and say who smashed the windows of the synagogue in 1938. Eventually he was given the O.K.

For his efforts, before his early death from cancer, Josef was awarded Germany’s highest honor: the Bundes Verdienstkreuz, the Medal of Merit. The State of Israel planted three trees in his honor.

There are more stories from Altenkunstadt, but we’ll save them for another time.

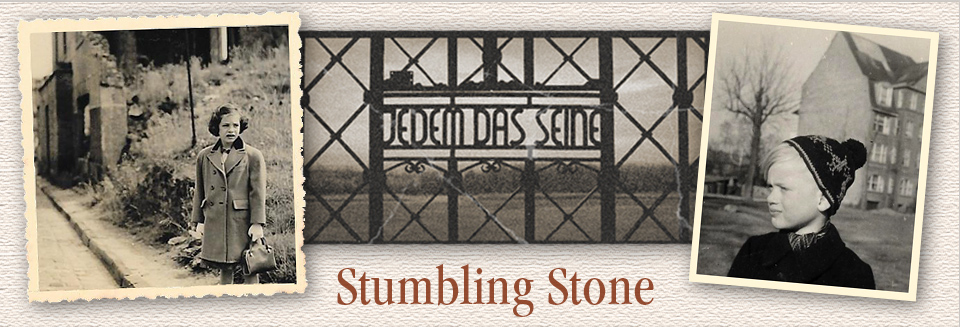

Rudi Raab and Julie Freestone are touring Germany with their novel, Der Stolperstein. It’s available in English as Stumbling Stone.