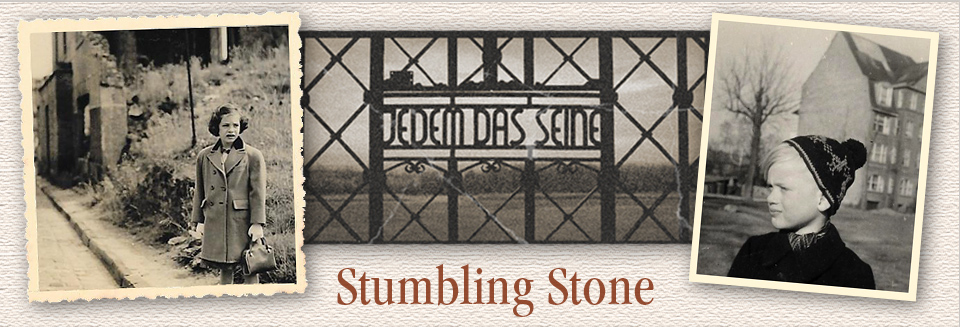

Do We Need Designated Story Tellers?

Book Tour: Bad Lippspringe, Germany, May 18. 2018

In my group that grapples with issues related to aging, we have at least one theme that recurs often: what to do with old letters and other mementos from lives we led years ago. Most of us agree we should get rid of them sooner rather than later so our families and friends who outlive us won’t have access to whatever secrets and thoughts we had then.

Imagine if some of those papers were documents that described what your parents or grandparents did in Germany during the Nazi years and showed that they weren’t in the resistance or engaged in some other heroic activity.

That issue was brought up in Bad Lippspringe this week when we did a book event sponsored by Buchlandlung Waltenmode, a book store.The reading with music was well attended and some interesting issues came up. This one was particularly intriguing because in the early years when Rudi and I went to Germany, no one even admitted having any papers or any relatives who were anything but farmers or foot soldiers who were conscripted against their will

That issue was brought up in Bad Lippspringe this week when we did a book event sponsored by Buchlandlung Waltenmode, a book store.The reading with music was well attended and some interesting issues came up. This one was particularly intriguing because in the early years when Rudi and I went to Germany, no one even admitted having any papers or any relatives who were anything but farmers or foot soldiers who were conscripted against their will

Rudi told the audience member, who was an old high school friend of his, that we donated some of the documents we had to the Holocaust Museum in Los Angeles.

One frustrating thing about this book tour of ours is the question and answer period. I’ve got my formal presentation down pretty well and as a result, many people in the audience think I speak German. They often ask long complicated questions. The acoustics in the venues aren’t always great and between not hearing well and different dialects of German, Rudi has all he can do to respond to the questions. There’s no real option for him to translate so I can add my thoughts because we’d be there all night.

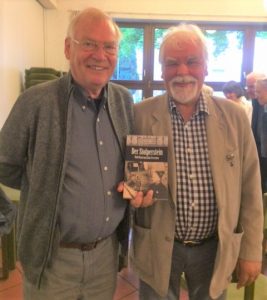

This delightful fried of Friedrich and Rebecca’s bought six copies of the book

So, I’ll tell you what I might have added—and it’s based on something our friend and editor Liz Rosner said when she spoke at the Commonwealth Club before we left. In her new book Survivor Café, she describes how the next generations deal with trauma like the Holocaust and the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The Japanese have embraced the concept of having someone become the designated storyteller for those who are getting old and dying. As the Germans try to embrace the scars of their past, ensuring that the experiences of the elders are captured would be a worthy use of those moldering documents.

Which is actually related to another question that came up that night. One woman asked whether we were finding Germany different on this trip than in the past. She said she thought things were actually getting worse in terms of whether Germans are willing to face up to the dark days of Nazism.

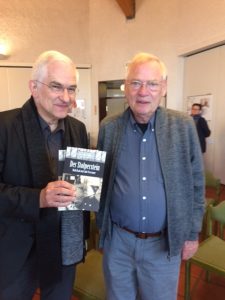

Such fun. Many places we’ve gone have given us gifts. In Bad Lippspringe we got lovely flowers and wine

This surprised us because it has seemed like every place we’ve been, people have spontaneously told us family stories, many that show complicity or at least a lack of courage in speaking out. But that may well be because people who are drawn to our events are likely to feel some kinship with the story of Rudi’s family: one brother a rebel and the other building his career on the principles Hitler espoused. They may be fascinated in the way people are when they drive by an accident by how we’re going to deal with difficult family issues.

Rudi Raab and Julie Freestone have been touring Germany with their novel Der Stolperstein, a car too small for their suitcases and boxes of books and back packs and miscellaneous stuff.