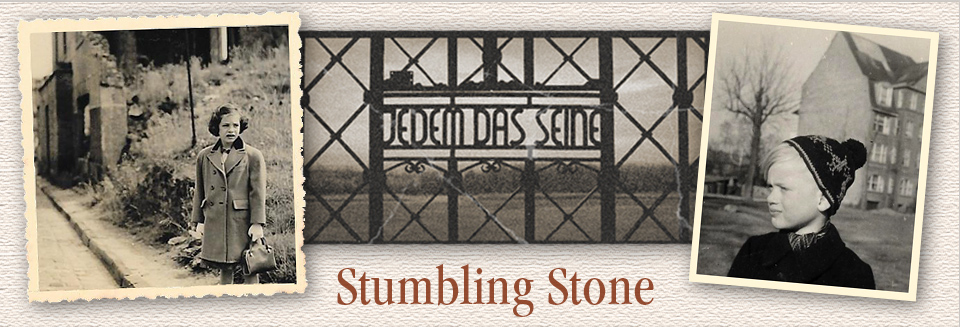

Hope in Spite of Everything

Stop Eight: Gauting, Germany, May 8, 2018

Rudi was pacing around, surveying the relatively small room, set up café style, with a bar, small tables and some chairs. It was 15 minutes before the event was to start and there was almost no one there. Not given to overstating, Rudi said, “This is going to be a disaster.”

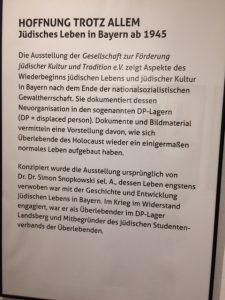

Far from it. To start with, our book reading in Gauting, outside of Munich, was on the site of what was a camp for DPs—displaced persons—after World War II. I had a particular affinity for it because my father, an immigration lawyer, was a senior official in charge of a resettling Jews and other victims of the Nazis. Although he worked at Camp Grohn in Bremen. I imagined as I walked around the museum at BOSCO, the civic and cultural center, that he might have been there in Gauting in 1948-1952. There was an exhibit called “Hope in Spite of Everything” about the DPs.

The exhibit in Gauting is titled “Hope in Spite of Everything”

Allied soldiers greet liberated prisoners and an article in Yiddish accuses the Nazis of murder

Rudi and Julie in Gauting (from Bosco Nach(t)kritik online)

When my family lived in Germany during my father’s assignment there, my mother wrote many letters describing life in those DP camps. It wasn’t pleasant. Those victims, many liberated from concentration camps and dealing with the devastating loss of their families, villages, culture and livelihoods, lived packed into cramped quarters with few belongings. The exhibit at Gauting showed the ways in which the DP’s tried to establish some normalcy, launching a newspaper and putting on plays. There are photos of the camps being liberated and the Allied soldiers mixing with the survivors.

It wasn’t until recently, when our friend Oliver Pollak, a Jewish scholar, gave us a book about the DPs, that I realized what an overwhelming challenge the Allies had in terms of dealing with staggering numbers of homeless people—and prisoners of war. It seems that at least at the beginning, there were many mishandled and inhumane parts of the operation. My father never talked about that. (I never asked). If I were home with Oliver’s book and not writing “on the road,” I’d throw in a few facts. Maybe later.

In the end, about 30 people came to the Gauting event and after it was over, they were in no hurry to leave. They clearly loved our story and the combination of the music and story evoked a passionate comment from one of the audience members. They wanted to tell us how remarkable it was that I learned German in such a short time (Rudi tells them I started my lessons in September. I don’t know German. Only the script for the book event. A number of them spoke English, a few were American-born and in whatever language, they wanted to share their stories.

Just an aside: This is the first time anyone has actually articulated how amazing the combination of our reading and Friedrich Edelmann and Rebecca Rust’s music blend to present a smooth and impactful program. It was actually this unique joining of our prose and compositions from Jewish composers that led Rudi to translate our novel Stumbling Stone into German. We did an event at Book Passage in Corte Madera, California with Friedrich and Rebecca about two years ago. We were all delighted with how it went, and Friedrich said we had to come to Germany to do a tour there. Rudi pointed out we only had a book in English. A year later, with much help from wonderful German speaking editors, we had Der Stolperstein.

My first assignment in our German book reading is to suggest to the audience—in German of course—that they should imagine the music as the sound track to a movie that would be made of the book. There is actually a cello solo by Rebecca after we describe the consequences of Gerhard’s resistance to the Nazis that the cello seems to be weeping. And wailing.

Anyway, back to the stories we heard in Gauting. One woman said she had an aunt who had been very definitely a Nazi. In fact, she had a high-level job. Based on what she told Rudi (I didn’t understand), he concluded the relative might have been a guard in a Nazi concentration camp.

Anyway, back to the stories we heard in Gauting. One woman said she had an aunt who had been very definitely a Nazi. In fact, she had a high-level job. Based on what she told Rudi (I didn’t understand), he concluded the relative might have been a guard in a Nazi concentration camp.

It’s almost as if Rudi’s saying, “My father was a high-ranking Nazi” and, when asked, acknowledging that his father never renounced Hitler and his philosophy, that we have freed up some Germans to talk honestly about their own family histories.

Julie Freestone and Rudi Raab are halfway through their German book tour with their novel Der Stolperstein. They will be taking a break for a few days. Their next reading is in Ulm on Monday.