We Go Back in Time

Ludmila Renkatschisehskaja, Rudi and Yulia Merzogitova at Ariowitsch-Haus in Leipzig

A Community Rises from the Ashes

It almost seemed eerie that we found parking in front of a sign that said “Gerhard”, advertising a labor lawyer’s office and right near Ariowitsch-Haus in Leipzig, where our second book event was. Was it a good omen? We were there in that city because we were to talk about our novel, a literary memorial to Rudi’s uncle Gerhard.

If so, it probably wasn’t a good omen. First, the PowerPoint projector wasn’t compatible with our laptop, even though we had brought a special cable. That problem was solved when someone brought a different laptop. Sighs of relief all around until Rudi knocked over a glass of water (one of the six glasses he drinks a year). Paper towels and finally a mop. Then we looked at the clock and realized it was time to start. A bigger problem. Only two women, who’d come by streetcar, and two volunteers from the center were in the audience. The two men who helped set up didn’t stay to listen.

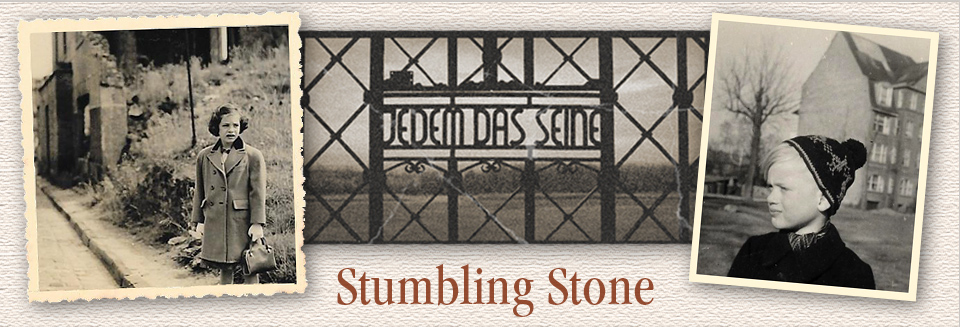

Once, a year or so into our life with Stumbling Stone, the American version of our German Der Stolperstein, we went to Montana to visit a friend, who arranged for us to do a reading at the library in Helena. Only she and the librarian came. Then we met Friedrich Edelmann, bassoonist, and his wife Rebecca Rust, cellist, and they told us that in their years of performing, they developed a philosophy that if there were at least as may people in the audience as on the stage, it was a success. And our friend, Professor Emerita and author Ruth Rosen, shared her experience of turning an audience into a seminar when the turnout was dramatically small.

Rising from the Ashes

In fact, the trip to Leipzig turned out to be a winner for several reasons. The volunteers at the culture and meeting center for Jewish issues were emigres from the former Soviet Union. They have been in Germany less than 20 years and speak fluent German. Those two and the other women listened avidly and were quick to identify commonality—my mother was born in what was probably Ukraine and so was one of the women. The question-and-answer period turned into a dynamic dialogue, rich with their shared history.

They were anxious to help us understand the Jewish community in Leipzig that was once 14,000, decimated to 30 people after the Nazis and now has about 1300, bolstered by an influx of Russian and other immigrants from former Communist countries. Nearly a third of the survivors after the war in Leipzig were Chinese Jews, related to a Chinese man who had settled in the city and married a local Jewish woman. While they didn’t seem to think Gerhard’s story was a big deal—they had all lost someone to the Nazis—they were charmed by our love story.

Besides the experience at Ariowitsch-Haus, below is why the very long drive to Leipzig and then back to Bavarian where we will have two weeks of events, worked for Rudi. The rest of this blog is his.

Rudi at the Square in Leipzig

In our living room in Richmond, California, is a print made from a drawing of the grand entry into Leipzig of the sovereigns after the victory over Napoleon in 1813. The original, a centerfold of a newspaper picture that appeared in London in 1814, depicts the central market square of Leipzig, with city hall and several buildings. It shows the Czar of Russian, the kings of Sweden, Saxony, Hesse and Bavaria and their entourages with flags and on horseback. The square is surrounded by a thousand Saxon dragoons and many more onlookers, each figure painstakingly painted in color.

At night I went to the square, two minutes from our hotel. While one third was bombed in WW II, the surviving part still looks like the painting in our living room. I imagined myself among the horses and flags of the victory parade. Then I walked onto a side street from where, in my painting, the participants came from. I wanted to see how they staged the parade and what they saw when they were waiting to enter. On either side, I saw incredible Renaissance buildings, intact and well maintained. The surface of the street was the original cobblestone. History: am I part of it or am I just experiencing it?

Finding Bach

On a short walk near our hotel looking for a convenient parking lot, we saw a medium-sized, old church.

St. Nicolas Church in Leipig

. The doors, which were open, had a sign that said “St Nicholas”. Inside I saw a Gothic church converted into Baroque and I heard on the emporium behind me a magnificent church choir signing a Baroque chorale. Then I realized that St. Nicholas was one of the two main churches in Leipzig where Johann Sebastian Bach was employed to compose one cantata each Sunday. His Christmas Oratorio was played here as well as in the other church and conducted by him on six consecutive Sundays. While searching for a parking space, I had stumbled upon the Holy Grail of music.

My grandfather’s house

Back to our book. One of the main scenes plays in the attic of what was my grandfather’s house in Leipzig. It is there that Karl and Sarah discover the dark mystery of Gerhard. We went to the house where the scene took place, only a short distance from our hotel. We looked up at the attic where the couple glean important information. Upon leaving, we took the path that Sarah and Karl walked toward the streetcar tracks to find dinner. I realized this was the route I strolled as an 11-year-old with my grandfather and which he took every

Grandfather’s house in Leipzig – the attic

day to work. The streetcar stop is still there. It was a walk back in time.

Julie Freestone and Rudi Raab are on a book tour in Germany for Der Stolperstein and are blogging as they go. Please excuse any minor errors we attribute to less-than-ideal writing conditions and other assorted excuses.